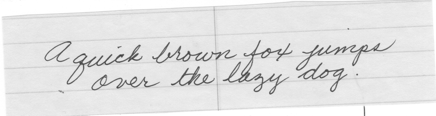

Since this is National Handwriting Day, it seems like a good time to talk about whether or not we should teach cursive handwriting in elementary school. Almost everyone engaged in the debate, whether pro or con, assumes that a “cursive” handwriting style is one in which all letters are joined with swoops and festooned with loops. It is true that this is what millions of kids in U.S. schools have been taught over the years. The variation of looped cursive I was taught (the Palmer Method) looks like this:

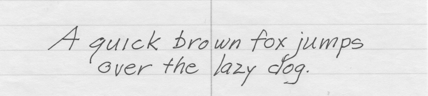

But “cursive” simply means a “running” hand, in which pen lifts are minimized. Fortunately, there is a preferable cursive alternative to the familiar looped varieties. For the past several weeks, I have been teaching myself cursive Italic handwriting with the aid of a workbook. This is the system of handwriting that is taught in European schools and in some private and US public schools as well. It is not a new idea, by any means. Italic handwriting has its roots in the Renaissance. Sometimes the old ways are the best, in this case really old.

There are no loops in Italic handwriting, and not all letter combinations are joined. Yet cursive Italic provides the writer with the means of writing rapidly and consistently.

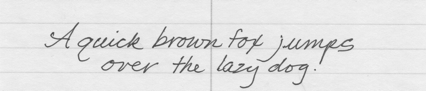

Perhaps the most important aspect of the Italic is that children transition from print to cursive without having to learn a whole new set of letter forms, as they do with a looped cursive hand. Poor little kids. Just when they are getting pretty good at printing, we start all over, usually in third grade, which requires them essentially to unlearn what they ‘ve been doing and learn something entirely different. It’s no wonder that so many opponents of “cursive” are so vehement in their opposition.The printed form that precedes looped cursive involves several pen strokes and is written with the paper held vertically. Sometimes called “ball and stick,” it looks like this:

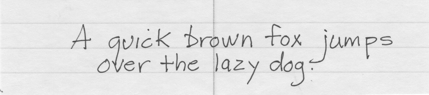

The printed form of Italic, on the other hand, is slightly slanted, just like the cursive form, and many of the letters are formed with only one stroke of the pen. The transition to the cursive form of Italic occurs in second grade when children are taught to join the letter forms they already know. This is printed Italic:

But why teach cursive handwriting at all? Do we really need it?

This is the argument opponents of cursive handwriting make: They say we don’t need to write by hand because nowadays we almost always communicate written language with the aid of an electronic device. When we need to communicate by hand, we can just print. We should not waste class time teaching something we don’t need.

But that is a very narrow definition of “need.” There is some evidence that the fine muscular control demanded of those learning to write rapidly and continuously by hand yields benefits far beyond the ability to produce a grocery list.There is apparently a vital connection between the brain and the hand that comes into play when one writes connecting letters. I think that this is where the most powerful argument for retaining cursive handwriting in the classroom resides.

There is no doubt that the writing of cursive requires different, more complex movements than tapping a keyboard or printing unconnected letters. The personal experience of those of us who write a lot by hand and the experience of many teachers suggest that the ability to write a flowing hand facilitates creativity, helps memory and promotes learning.

So I say let’s get rid of the wasteful practice of teaching ball and stick printing , drop the loop-de-loop form of cursive that has given so many people fits, and introduce a more efficient, simpler way of teaching kids to connect their letters and eventually develop a mature, legible, and graceful cursive hand.

I intend to return to this subject in future posts. I am particularly interested in finding out what research has been done on the brain/hand connection and how it might influence our opinion about the need for cursive writing. If you’d like to follow along, type your email in the “follow” box and you will receive all future posts by email. Or you can bookmark this site and check in from time to time.

And I’d love to hear your ideas about cursive in our schools. Just leave your comment below. For more on cursive handwriting, type the word “cursive” in the search box.

The workbook I am using to learn Italic is Write Now by Barbara Getty and Inga Dubay. It is designed for the use of adults who want to improve their handwriting.